Health as an Investment Good

Grossman’s model revolutionizes the understanding of health by framing it not merely as a consumption good, providing immediate satisfaction, but as a form of capital—an investment that yields future returns. Unlike purchasing a car for immediate use (consumption), investing in health generates benefits that extend over time, enhancing productivity and overall well-being. This perspective shifts the focus from immediate gratification to long-term gains, influencing individual choices about health behaviors and healthcare utilization.

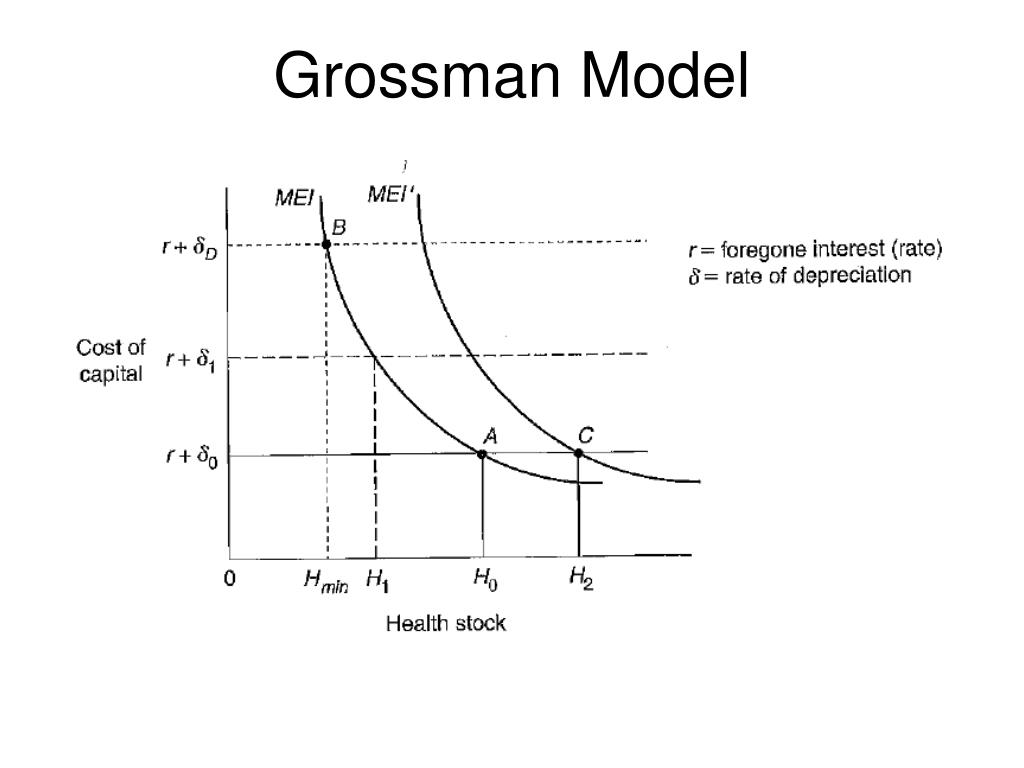

The core of Grossman’s model lies in the concept of health capital. Health capital refers to the stock of health an individual possesses at any given time. This stock is not static; it can be increased through investments in health-enhancing activities or depleted through illness, aging, or unhealthy behaviors. The higher the stock of health capital, the greater an individual’s productivity, longevity, and overall quality of life. This capital, therefore, is a crucial determinant of both economic and non-economic outcomes.

Health Capital and its Determinants

Grossman’s model posits that health capital is influenced by various factors, including investments in health-enhancing activities and the impact of aging and disease. Individuals make conscious choices regarding their health investments, balancing the costs and benefits of these actions. These investments can involve tangible expenses like medical care, gym memberships, or healthy food, but also intangible ones such as time spent exercising or avoiding risky behaviors. The model acknowledges that health capital depreciates over time, requiring ongoing investment to maintain or improve it. The rate of depreciation varies based on factors such as age, lifestyle, and genetic predisposition.

Examples of Investing in Health Capital

Investing in health capital takes many forms. For instance, choosing to quit smoking reduces the rate of health capital depreciation, extending lifespan and reducing the risk of numerous health problems. Regular exercise builds health capital by improving cardiovascular fitness, strengthening the immune system, and enhancing overall physical and mental well-being. Seeking preventative medical care, such as annual check-ups and vaccinations, helps detect and treat potential health issues early, preventing more serious and costly problems later. Similarly, investing in a healthy diet provides the body with the necessary nutrients to function optimally, contributing to a higher stock of health capital. A college student choosing to forgo late-night partying to get sufficient sleep is another example, prioritizing health capital accumulation over immediate gratification. These choices, though seemingly small individually, collectively contribute significantly to an individual’s long-term health and well-being.

The Demand for Health

Grossman’s model posits that individuals demand health as an investment good, contributing to their overall productivity and well-being. Understanding the factors influencing this demand is crucial for designing effective health policies and interventions. The demand for health, unlike many other goods, is intricately linked to individual characteristics, lifestyle choices, and access to healthcare resources.

The demand for health is a complex interplay of several factors. It’s not simply a matter of wanting to be healthy; it’s a multifaceted decision influenced by various personal and external pressures.

Factors Influencing the Demand for Health

Several factors significantly influence an individual’s demand for health. These factors interact dynamically, creating a unique health-seeking profile for each person. A key consideration is the perceived trade-off between health investments (e.g., healthy food, exercise, medical care) and other consumption choices.

- Income: Higher income generally allows individuals to afford better healthcare, healthier food choices, and fitness activities, increasing their demand for health.

- Price of Health Inputs: The cost of healthcare services, healthy food, gym memberships, and other health-related goods and services directly impacts the affordability and thus, the demand for health. High prices can deter individuals from seeking preventative care or making healthy lifestyle choices.

- Education and Information: Individuals with higher levels of education and access to reliable health information tend to make more informed choices about their health, leading to a potentially higher demand for preventative care and healthy lifestyles.

- Time Constraints: The time required for exercise, healthy meal preparation, and medical appointments can influence the demand for health, particularly for individuals with busy schedules.

- Age and Health Status: As individuals age, their demand for health often increases due to a higher susceptibility to illness and a greater need for preventative and curative healthcare. Pre-existing health conditions also significantly increase the demand for healthcare services.

- Preferences and Beliefs: Personal preferences, cultural beliefs, and perceptions of health risks all play a role in shaping an individual’s demand for health. Some individuals may prioritize health over other goods, while others may place less emphasis on it.

Comparison of Health Demand with Other Goods

The demand for health differs significantly from the demand for typical goods and services. While the demand for most goods can be easily substituted (e.g., choosing one brand of cereal over another), health is often viewed as a non-substitutable good. Its value is tied to overall well-being and future productivity, rather than immediate gratification. The demand for health is also influenced by factors that are not typically considered in the demand for other goods, such as age, genetics, and access to healthcare. Furthermore, the demand for health is often characterized by information asymmetry; individuals may not fully understand the risks and benefits of different health interventions, leading to potentially suboptimal decisions.

Hypothetical Scenario: Age and Health Demand

Consider three individuals: a 25-year-old, a 45-year-old, and a 65-year-old, all with similar incomes and access to healthcare. The 25-year-old may prioritize immediate consumption, placing less emphasis on preventative health measures. Their demand for health might be primarily driven by acute needs, such as treating injuries or illnesses. The 45-year-old, possibly facing increased work and family responsibilities, might exhibit a higher demand for preventative care to maintain productivity and well-being. They might invest in regular checkups, healthy eating, and exercise to avoid future health issues. The 65-year-old, potentially facing age-related health challenges, might demonstrate the highest demand for healthcare services, focusing on managing chronic conditions and ensuring a comfortable quality of life. This scenario highlights how age significantly shapes the demand for health, reflecting changing priorities and health needs across the lifespan. This is a simplified example; individual circumstances and personal preferences would naturally add further complexity.

Health Production and Inputs: What Is Grossman’s Model In Relation To Health

Grossman’s model views health not merely as a state of being, but as a good produced through the investment of various inputs. Understanding these inputs and their interplay is crucial to comprehending how individuals invest in and achieve better health outcomes. This section details the key inputs in Grossman’s model and analyzes their impact on health production.

What is grossman’s model in relation to health – The production of health, according to Grossman, is not a passive process but an active one requiring conscious investment of time, resources, and effort. Individuals, as rational actors, weigh the costs and benefits of these investments to maximize their health stock – a concept representing an individual’s overall health status.

Inputs in Health Production

Several factors contribute to the production of health within Grossman’s framework. These inputs can be broadly categorized and their impact on health outcomes is multifaceted and often interdependent.

| Input | Description | Source | Impact on Health |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Care | Includes preventative care (vaccinations, screenings), treatment of illness and injury (doctor visits, hospital stays, medication), and rehabilitative services. | Healthcare system, private insurance, government programs | Directly improves health by treating illness and injury, and indirectly by preventing future health problems through preventative care. The effectiveness varies depending on the type and quality of care. |

| Investment in Health | This encompasses actions individuals take to improve their health status, such as regular exercise, healthy diet, stress management, and avoidance of risky behaviors like smoking or excessive alcohol consumption. | Individual effort, self-discipline, access to healthy options (e.g., gyms, healthy food) | Significantly impacts long-term health outcomes. Regular exercise strengthens the cardiovascular system, while a healthy diet provides essential nutrients. Stress management techniques can reduce the risk of chronic diseases. |

| Education | Education equips individuals with knowledge about health and well-being, enabling them to make informed decisions regarding their health. This includes understanding health risks, preventative measures, and the benefits of healthy lifestyle choices. | Formal education (schools, universities), informal learning (media, community programs) | Improves health outcomes by fostering informed decision-making. Educated individuals are more likely to adopt healthy behaviors and seek appropriate medical care. |

| Environmental Factors | These encompass aspects of the environment that affect health, such as air and water quality, sanitation, and exposure to pollutants. Individuals have limited control over these factors. | Government regulations, industrial practices, natural environment | Can significantly impact health, both positively and negatively. Clean air and water improve respiratory and digestive health, while pollution can cause various health problems. |

Changes in these inputs directly affect health outcomes. For example, increased investment in medical care can lead to improved treatment of diseases and better health outcomes. Similarly, an increase in education regarding healthy lifestyles can result in improved dietary habits and increased physical activity, positively impacting long-term health. Conversely, a deterioration in environmental factors, such as increased air pollution, can lead to a decline in overall health.

Grossman’s Model and Health Policy

Grossman’s model, while a simplification of human health behavior, offers valuable insights for shaping effective health policies. By framing health as an investment good, it provides a framework for understanding individual choices regarding health investments and their implications for societal well-being. Analyzing how individuals invest in their health – through preventative measures, healthcare utilization, and lifestyle choices – allows policymakers to design interventions that encourage healthier behaviors and improve overall population health outcomes.

Grossman’s model suggests that health policies should focus on factors influencing both the production and demand for health. This includes addressing determinants of health beyond just healthcare access, such as education, income, and environmental factors. The model also highlights the importance of considering the time costs associated with health investments and the interplay between health and productivity.

Implications of Grossman’s Model for Health Policy Decisions

The model’s core tenets directly influence policy design. For instance, understanding that health is an investment good suggests that policies promoting health improvements in the younger population yield long-term economic benefits through increased productivity and reduced healthcare costs later in life. This supports investments in childhood vaccinations, health education programs, and initiatives promoting healthy lifestyles from a young age. Conversely, neglecting preventative health measures can lead to higher healthcare expenditures and reduced productivity in the long run. Policies that fail to account for these long-term effects may be economically inefficient. For example, a policy solely focused on treating chronic illnesses, without addressing their underlying causes through preventative measures, might be less effective and more costly in the long run compared to a holistic approach incorporating both treatment and prevention.

Examples of Health Policies Consistent with Grossman’s Model, What is grossman’s model in relation to health

Several health policies align with Grossman’s model’s predictions. Public health campaigns promoting healthy eating and exercise directly address the inputs into health production within the model. Subsidies for preventative healthcare services, such as vaccinations and screenings, lower the cost of health investment, thereby potentially increasing the demand for health. Similarly, policies aimed at improving education levels, particularly health literacy, can enhance individuals’ ability to make informed decisions about their health, leading to better health outcomes. Government regulations aimed at improving air and water quality also contribute to better health outcomes by impacting environmental inputs to health production. These policies recognize that health is not solely determined by individual choices but is also influenced by environmental and socioeconomic factors.

Limitations of Using Grossman’s Model to Guide Health Policy

While insightful, Grossman’s model has limitations. It simplifies complex human behavior and may not fully capture the nuances of individual health decisions. The model assumes perfect information and rational decision-making, which may not always hold true in reality. For example, individuals may underestimate the long-term health consequences of unhealthy behaviors or lack the resources to make optimal health investments. Furthermore, the model struggles to fully address issues of health inequality and access to healthcare, especially in contexts of significant socioeconomic disparities. The model’s focus on individual investment might overshadow the importance of social determinants of health, such as poverty, discrimination, and lack of access to healthcare services. Therefore, relying solely on Grossman’s model to inform health policy could lead to incomplete or even inequitable solutions. Policymakers need to consider the model’s limitations and incorporate other perspectives and data to develop comprehensive and effective health policies.

Tim Redaksi