Defining Epidemiology and Mental Health

Epidemiology is the study of the distribution and determinants of health-related states or events in specified populations, and the application of this study to the control of health problems. It’s a cornerstone of public health, providing the framework for understanding and addressing health issues at a population level, not just individual cases. This includes identifying risk factors, tracking disease trends, and evaluating interventions. Mental health, in contrast, refers to a person’s overall psychological well-being, encompassing their emotional, psychological, and social capabilities. It influences how we think, feel, and act, and it helps determine how we handle stress, relate to others, and make choices. The intersection of these two fields is crucial for understanding and managing the significant public health burden posed by mental health disorders.

Core Principles of Epidemiology and its Scope

Epidemiology relies on several core principles. First, it emphasizes a population perspective, analyzing patterns of disease across groups rather than focusing solely on individual cases. Second, it employs systematic data collection and analysis, using statistical methods to identify trends and risk factors. Third, it relies on a multidisciplinary approach, drawing on knowledge from various fields like medicine, sociology, and statistics. The scope of epidemiology is broad, encompassing infectious and chronic diseases, injuries, and even social determinants of health. It plays a critical role in disease surveillance, outbreak investigation, and the evaluation of public health interventions, including those targeted at mental health conditions. For instance, epidemiological studies have helped identify risk factors for depression, such as poverty and social isolation, leading to targeted public health programs designed to address these factors.

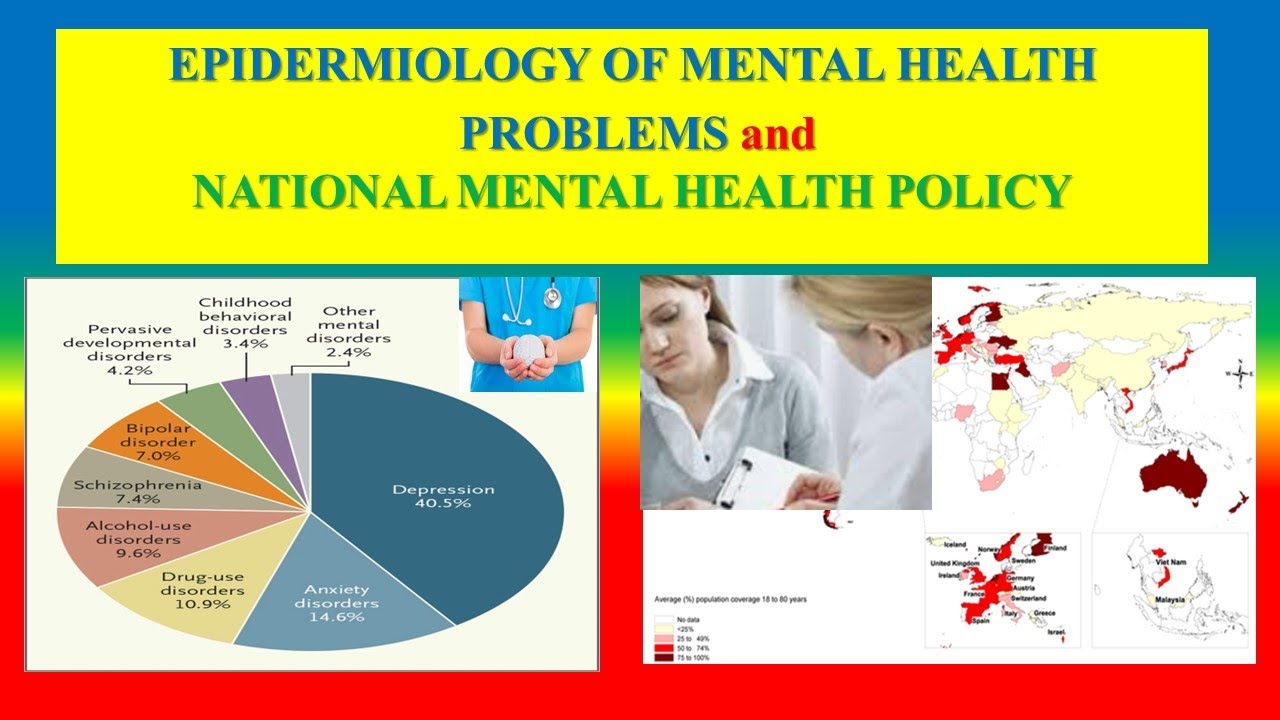

Classifications and Definitions of Mental Health Disorders

Mental health disorders are broadly categorized using systems like the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) published by the American Psychiatric Association and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) published by the World Health Organization. These manuals provide standardized criteria for diagnosing various conditions, ensuring consistency in clinical practice and research. Definitions of specific disorders, however, are continually refined as our understanding of mental illness evolves. For example, the DSM-5 significantly altered the diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder, reflecting advances in research and clinical understanding. The classifications within these manuals cover a wide range of conditions, including mood disorders (e.g., depression, bipolar disorder), anxiety disorders (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder), psychotic disorders (e.g., schizophrenia), and personality disorders. Each disorder has its own specific diagnostic criteria, outlining the symptoms and their duration necessary for a diagnosis.

Methodologies in Studying Physical and Mental Health

While both physical and mental health research utilize epidemiological methods, there are important differences. Studies of physical health often rely on readily available biological markers (e.g., blood pressure, cholesterol levels) and objective diagnostic tests (e.g., X-rays, blood tests). Mental health research, however, often relies on self-reported symptoms, clinical interviews, and behavioral observations, making the assessment process more subjective and potentially prone to bias. This necessitates the use of validated assessment tools and rigorous statistical techniques to minimize measurement error and confounding factors. Furthermore, the study designs employed can vary. While randomized controlled trials are frequently used in physical health research to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, these designs can be more challenging to implement in mental health research due to ethical considerations and the complexity of mental health conditions. However, both fields utilize cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies to investigate risk factors and disease patterns. For example, a cohort study might follow a group of individuals over time to assess the incidence of depression in relation to exposure to stressful life events.

Challenges and Limitations: Is Mental Health Part Of Epidemiology

Accurately applying epidemiological methods to mental health presents unique and significant hurdles. The complexities inherent in mental illness, coupled with the limitations of current diagnostic tools and data collection methods, create substantial challenges in understanding its prevalence, risk factors, and effective interventions. These challenges impact the validity and reliability of epidemiological findings, ultimately hindering our ability to develop and implement effective public health strategies.

The accurate measurement and diagnosis of mental health disorders for epidemiological studies is fraught with difficulties. Unlike many physical illnesses with readily observable symptoms and objective diagnostic tests, mental health disorders often involve subjective experiences and complex symptom presentations. Diagnostic criteria themselves can be ambiguous, leading to inconsistencies in diagnosis across clinicians and settings. Furthermore, the stigma associated with mental illness can lead to underreporting and underdiagnosis, particularly in certain populations or cultural contexts. This underreporting skews epidemiological data, creating an inaccurate picture of the true prevalence of mental health disorders.

Diagnostic Challenges and Measurement Error

The reliance on self-reported data in many epidemiological studies introduces the potential for recall bias and social desirability bias. Individuals may not accurately recall past experiences or may be reluctant to disclose sensitive information about their mental health, leading to inaccurate or incomplete data. For example, studies relying solely on self-reported anxiety levels may underestimate the true prevalence of anxiety disorders, as individuals might downplay their symptoms due to stigma or a lack of awareness. Similarly, diagnostic interviews, while considered more reliable than self-report questionnaires, are still susceptible to interviewer bias and the subjective interpretation of symptoms. The lack of standardized diagnostic tools across different settings and cultures further complicates cross-cultural comparisons and meta-analyses of epidemiological data. Standardized diagnostic tools like the DSM-5 and ICD-11 strive to address this but do not fully eliminate the inherent subjectivity in mental health diagnoses.

Biases Affecting Epidemiological Findings

Several biases can significantly affect the validity and reliability of epidemiological findings in mental health research. Selection bias can occur when participants in a study are not representative of the broader population, leading to skewed results. For instance, studies relying on convenience samples (e.g., university students) may not accurately reflect the mental health status of the general population. Publication bias, where studies with statistically significant results are more likely to be published than those with null findings, can also distort the overall understanding of a phenomenon. This can lead to an overestimation of the effectiveness of certain interventions or an underestimation of the prevalence of certain disorders. Confounding factors, such as socioeconomic status or access to healthcare, can also influence the results, making it difficult to isolate the true effects of specific risk factors. For example, a study examining the relationship between unemployment and depression might fail to account for the impact of pre-existing mental health conditions on employment status, leading to an inaccurate conclusion about causality.

Limitations of Current Epidemiological Approaches

Current epidemiological approaches often struggle to capture the complex interplay of factors contributing to mental health. While epidemiological studies are excellent at identifying correlations between risk factors and mental health outcomes, they often fall short in establishing causality. The complex interplay between genetic predispositions, environmental factors (such as childhood trauma or stressful life events), and social determinants of health makes it challenging to disentangle the relative contributions of each factor. Moreover, many epidemiological studies focus on single disorders in isolation, neglecting the high degree of comorbidity (the co-occurrence of multiple disorders) that is characteristic of mental illness. A person experiencing depression may also be experiencing anxiety, substance abuse, or other conditions, and studying these conditions in isolation may not reflect the reality of clinical presentations. Longitudinal studies, while valuable, are expensive and time-consuming, limiting the scale and scope of research.

Future Directions

The field of mental health epidemiology is poised for significant advancements, driven by both methodological innovations and a growing recognition of the profound impact of mental illness on individuals, communities, and global health. Future research will increasingly focus on refining existing methodologies, exploring new data sources, and leveraging technological advancements to better understand and address the complex interplay of factors contributing to mental health outcomes.

Emerging trends and research areas are rapidly expanding the scope of mental health epidemiology. This includes a stronger focus on precision medicine approaches, tailoring interventions to specific subgroups based on genetic predispositions, environmental exposures, and lifestyle factors. Furthermore, research is increasingly examining the life-course perspective, tracing the development of mental disorders across the lifespan and identifying critical periods of vulnerability. The investigation of the social determinants of mental health, encompassing socioeconomic status, education, and social support, is also gaining momentum, aiming to address health inequities and improve population-level mental health. Finally, the study of the complex interplay between physical and mental health is becoming increasingly important, recognizing the bidirectional relationship between conditions like cardiovascular disease and depression.

Technological Advancements in Mental Health Epidemiological Research, Is mental health part of epidemiology

Big data analytics, encompassing the collection, storage, and analysis of massive datasets, offers unparalleled opportunities to identify patterns and risk factors for mental health disorders that would be impossible to detect using traditional methods. For example, analyzing social media data can provide insights into population-level mental health trends and identify emerging crises. Artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms can be used to improve the accuracy of diagnostic tools, predict treatment response, and personalize interventions. AI-powered natural language processing can analyze large volumes of clinical notes and research papers, accelerating the pace of scientific discovery. Machine learning techniques can be applied to identify individuals at high risk of developing mental health disorders, enabling proactive interventions and improved preventative care. For instance, AI algorithms trained on electronic health records could identify individuals with a combination of risk factors for depression, allowing for early intervention and potentially preventing the onset of the disorder.

Integration of Epidemiological Data with Other Health Data Sources

Integrating epidemiological data with other health data sources, such as electronic health records, claims data, and genetic data, can provide a more holistic understanding of mental health. Linking mental health data with data on physical health conditions can reveal the complex relationships between physical and mental illness. For example, integrating data on depression with data on cardiovascular disease could reveal shared risk factors and inform strategies for integrated care. Combining mental health data with socioeconomic data can illuminate the social determinants of mental health and inform targeted interventions to address health inequities. The integration of various data sources, through secure and ethical data linkage practices, promises a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the multifaceted nature of mental health and its impact on overall well-being. This integrated approach can help researchers develop more effective prevention and treatment strategies and improve population-level mental health outcomes.

Tim Redaksi